British Beef

Tom Cook on the enduring Larkin-Hill squabble

‘STILL GOING ON, all of it, still going on!’ Three decades of death notwithstanding, Philip Larkin continues to threaten the pedigree of British poetry – at least according to Sir Geoffrey Hill. The Oxford Professor of Poetry used his valedictory lecture on May 5, 2015 to tell the world, once again, why it is so wrong with the mere ‘university wit’: ‘His work is rated so highly across the literary board,’ said Hill, ‘because a large consensus has been persuaded by critical opinion that certain mediocre poems are outstanding.’ Hill goes on, insisting that Larkin’s now-totemic (I almost wrote iconic) ‘Church Going’ is not ‘a masterpiece of our times’ but a strain on the intelligent reader’s patience.

Philip Larkin

There are questions of temperament here. Hill has a complex, meaningful relationship with the Anglican church Larkin apparently mocks in the poem (even though Larkin was living in Belfast at the time of its composition, and there is little in the poem that suggests it refers to a specific country or denomination). Hill also has no patience for Larkin’s reactionary public persona, reading the notorious 1955 myth-kitty statement – ‘every poem must be its own sole freshly created universe, and therefore have no belief in ‘tradition’ or a common myth-kitty or casual allusions in poems to other poems or poets’ – as artistic sacrilege. Despite his skill as a literary critic, teasing out nuance wherever it arises, he takes Larkin at surprisingly face value.

There are concessions: ‘Days’, ‘Going’, ‘Wants’, ‘Water’, ‘Solar’ and ‘The Explosion’ are all begrudged their excellence in the final Oxford lecture, and admiration is expressed for ‘Wedding-Wind’ and ‘Next, Please’ (though the latter ‘because it’s Hill-ish’) in a Telegraph interview. But where it counts, he ensures we know the hostilities are ongoing.

It isn’t the first time Hill has bristled in reaction to his late contemporary; nor is it a debate carried out on purely critical grounds. A self-described ‘freak survivor’ of the modernism Larkin affected to loathe, Hill is evidently still prickling after coming under attack in the poet’s posthumous Selected Letters: After A. N. Wilson pens a disparaging review of Andrew Motion’s Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry, Larkin is ‘cackling with sheer delight, except for [Wilson’s] implication that G. Hill and T. Hughes are any good.’ And in 1972, Larkin’s forthcoming Punch review of Cole Porter’s lyrics is awarded a decisive ‘Still, better than Mercian Hymns’ (Hill’s landmark volume of prose poems, released the previous year).

As the digs become public, Hill musters his defence. Noticing that Christopher Ricks – one of his staunchest admirers – has praised the ‘deplorable’ Larkin, Hill issues a corrective barbed footnote in a 2003 book of essays: ‘During his lifetime Larkin was granted endless credit by the bank of Opinion … The notion of accessibility of his work [sic] acknowledged the ease with which readers could overlay it with transparencies of their own preference.’

Ricks praises Larkin; Hill gets wind of Ricks’s praise and cannot bear the judgement; Hill snipes at Larkin and, years later, in the absence of Larkin, at anyone still listening who enjoys the man’s work. Britain has a longstanding tradition of such tiny, prattling wars, with poet A desperate to overturn poet B (even Shakespeare couldn’t quite keep thoughts of his ‘rival poet’ from the sonnets, likely a figure as estimable as Chapman, Drayton or Marlowe). That the island may be big enough for two or more such talents cannot be borne: the centrists cannot hold.

SO, WHEN HILL parades mere judgements of taste (I don’t like Larkin/his poems) as timeless aesthetic-moral principles (‘narrow English possessiveness’), the tactic is symptomatic: poets declare their presence by stamping their taste onto the work of their forebears; by urinating against the sacred tree. This can lead even our greatest poets into some strange territory. Hill acknowledges that ‘In rejecting the Larkin package I am made to reject Wilfred Owen too, and Blunden, and Gray,’ though this is all right because doing so makes him ‘beneficiary of Dr Johnson’s tacit approval’.

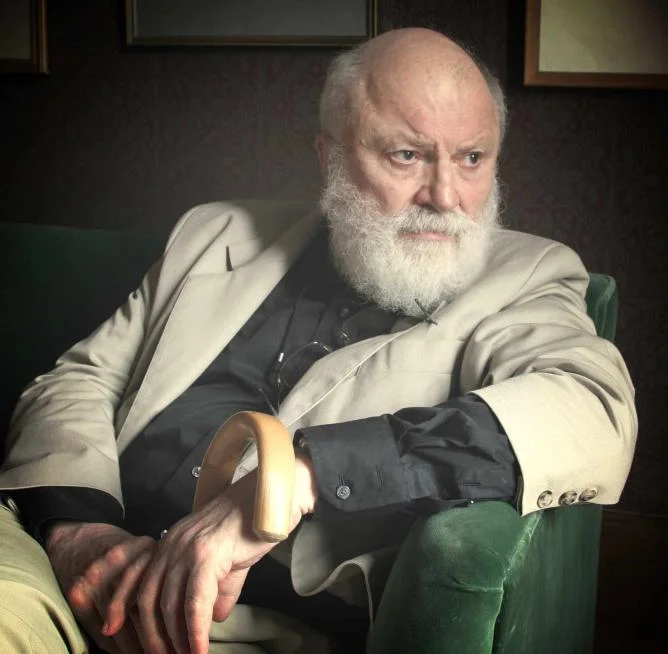

Geoffrey Hill

Similarly, Edward Thomas is not a war poet at all (a fair claim), nor a crafter of direct lyric verse, but ‘a metaphysical poet’ (a claim more loaded but also, when speaking of a twentieth-century poet, somehow less vital); someone concerned far more with intellectual-emotional dialogue than the rapid rattle of Ypres guns. Contributing to a recent festschrift on Thomas, Branch-Lines, it is clear that Hill likes and admires his work, presumably on such terms – a comrade firmly in the ancestry that nourishes the modernists and gives rise to Hill’s own high-church style:

I have always loved Edward Thomas’s poetry … I think he is a truly major minor poet like Wyatt. His influence on me, when I was fourteen or fifteen, was disastrous. I produced several very bad pastiches of his work, none of which I kept. By the age of sixteen I was an aggressive modernist … I think there is a real body politic element to all these people [connected to Thomas, including Housman, Butterworth and Gurney].

The pattern repeats equivalently elsewhere: reaching for his books – from Shakespeare to Hopkins, Hardy’s Dynasts, Eliot, Empson, Alun Lewis and more – Hill establishes himself in a strong tradition of English intellectual and moral poetry, taking aim along the way at all those who seem to contradict his position, among them the Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy. It is a war-cry, designed to ring from the dreaming spires and disturb history. Yet if I reach across my shelves from Hill (skimming by poets as various as Hughes, Walcott, Gunn, Sexton, Kinsella, Jennings and Ginsberg, all born in the years between them) and return to Larkin, a very different English canon emerges, though one characterised by his own equivalent vehemence.

Larkin’s Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse caused months of squabbling in the British press on its release in 1973. Like Hill’s lectures, it provides, as Heaney wrote at the time, insight as regards ‘the poetic aspirations and predilections of its editor’. The anthology is clear in its stylistic allegiances: as Larkin is by Hill, Eliot is begrudged the presence of his masterpieces, and Yeats gets a similarly strong look-in – but otherwise an excavated line runs from Hardy, Housman and Kipling up to Stevie Smith, Betjeman, Auden, Roy Fuller, Ewart, Amis, Larkin himself, Thwaite, Dunn, Hugo Williams, and the emergence of ‘the Liverpool boys’. Sturdy, plainspoken English stuff, and all of a piece with the simplicity and ‘authority of sadness’ Larkin recommended. But although Hardy was Larkin’s literary idol in later life, it is perhaps surprising to find both him and Hill rating the old man of Dorset so highly. Should two such divergent talents not, according to their own principle, reject such an overlap? Strange, too, noticing Larkin’s inclusion of ‘In Memory of Jane Fraser’, Hill’s searing lyric elegy for a woman who, unbeknown to its first readers, never existed; and the entirety of Walcott’s beautiful ‘Tales of the Islands’, and ‘A Letter from Brooklyn’.

Their common ground extends further still. The Oxford Book also takes in the poetry of the Great War: Hill’s ‘rejected’ Owen is there (seven poems) as is Siegfried Sassoon (also on seven), and Rupert Brooke does well (with six). The less clearly English, more modernist instincts of Rosenberg and Gurney have only three poems between them. So far, so distinct. But Edward Thomas, that Hillian ‘metaphysical’? More prominent than any other, his nine poems outnumber even those of Larkin’s beloved Stevie Smith, at a time when each was, arguably, minor enough to sideline if one so chose.

Reviewing William Cooke’s biography of Thomas in 1970, while compiling the Oxford Book, Larkin wrote,

As for the war, Thomas was not a war poet … The Army did not so much give him a subject as bring his proper subject, England, into focus … the England of 1915, of farms and men ‘going out’, of flowers still growing because there were no boys to pick them for their girls.

Just as for Hill, in Branch-Lines, Thomas is a metaphysical, an uncle of modernism, for Larkin he is grounded in the countryside, his heritage, his birthright English melancholia. Taste is a mirror, however complex the argument one builds to explain its instincts. Both poets place equal importance on Thomas, vying in their ways for his posthumous allegiance, for his endorsement of their own technique – and in so doing, both are seeing in his genius something of themselves.

“That the island may be big enough for two or more such talents cannot be borne: the centrists cannot hold”

This is, before anything else, very amusing: two of the greatest figures of postwar British poetry squabble like ducks chasing an unsunk crust. They agree in their reaction to consensus – not a war poet – but only in as much as this allows them to fence his redefinition off for their own ends, to bring his poetic authority onboard as proof that they, and they alone, possess the newfound key to the contemporary English line. As with their gossip and snideness about one another, their stylistic and historical crossfire is part of a much wider trend. Not only do the pair conform to a centuries-old tradition of poetic rivalry, they also embody a great irony: that – in establishing themselves in the public imagination – many of our poets must choose a lectern and preach, all the while disguising their much more interesting variety and artistic inconsistencies, often the very things their readers most admire.

Far from having ‘no belief in ‘tradition’ or a common myth-kitty or casual allusions’, Larkin’s ‘man next door’ voice is subtly interwoven with adapted modernist techniques: the annotations to his Complete Poems almost outweigh the original writing itself, and with good reason. And alongside all the complexity, Hill’s tendency to playfulness and direct, emotional address is more apparent the longer he is read, especially with each of his postmillennial books, where voices comic and tragic clash with each other across and within their poems. All in all, poets not only can’t trust one another, they can’t trust themselves. This whole notion of inherited, tussled-for and modified taste brings us straight back to ‘tradition’, and therein, of course, to Eliot’s ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’:

for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered; and so the relations, proportions, values of each work of art toward the whole are readjusted; and this is conformity between the old and the new.

This is precisely what is enacted in Hill’s proclamation of a modernist-centric tradition in which Edward Thomas is ‘a metaphysical poet’, Wilfred Owen ‘variable’, and a poem the word-child of a vortex; where ‘expressiveness’ is prioritised over ‘self-expression’, and Pound, Wyndham Lewis and their gang loom seriously large. It is also the mechanism apparently scorned by Larkin in his ‘Statement’, while in reality (unacknowledged out of tactics or ignorance by Hill) Larkin is engaged in precisely the same when he promotes Hardy, Owen, Sassoon, Smith, Brooke and Thomas while denouncing the ‘Celtic fever’ of Yeats and the unholy modernist trinity of Pound, Parker and Picasso.

Occasionally, this process of relation misfires, or turns rancid. A telling demonstration is the legacy of Plath. Crudely shaped to become the poster-child of madness, second-wave feminism, motherhood, domestic dejection and all other manners of social and personal subjectivity, she was branded a ‘raw’ confessionalist, in part due to her own identification, during an interview, with the work of Sexton and Lowell. However, equally ardently – almost in the same breath – she told the public,

I cannot sympathise with these cries from the heart that are informed by nothing except a needle or a knife, or whatever it is. I believe that one should be able to control and manipulate experiences, even the most terrific, like madness, being tortured, this sort of experience, and one should be able to manipulate these experiences with an informed and an intelligent mind.

Dead by the time her masterpiece Ariel launched her work to real success, she became the ultimate example of this tension between the poetry and the visible poet: the ultimate case of the appearances overtaking, and oversimplifying, readers’ perceptions of the verse; though in her case, it was an image promoted only somewhat by her, but very greatly by her readers in the vacuum left by her suicide. Had she survived her depression, she might’ve stood a far greater chance of ‘expressing’ her own position more clearly. As it was, her legacy was given over to agenda-crazed individuals of every stripe (mainly under the silence of Hughes), and we are only now beginning to re-place her where she began: with her own modification of the English-language line and as the author of great poems.

That said, stagnation can still set in when the poet lives a more average life – as it so very clearly has in the case of Hill, and had in Larkin before his comparatively early death. The poet (now established as an increment of tradition, a recent chapter of poetic canon) begins to turn their ire and authority against the young and the new, and accusations of heresy spring up hot and fast.

In Hill’s case, this has embodied most strongly as a subplot of the Oxford lectures: many of the young are inadequate or doomed, lured away from true, serendipitous poetic development by Duffy’s alleged interest in texting, the siren-song of creative writing courses, the ‘oligarchical commoditisation’ of language and the influence of certain poets, apparently like Larkin, encouraging ‘self-expression’ in place of ‘expressiveness’. The fact that Larkin, for example, felt obliged to tell a friend that her first novel leant too heavily on her emotions and experience to be good art, is not mentioned. Nor is a 1956 letter to his long-term, long-distance girlfriend Monica Jones worrying that a poem resisting him ‘is too true: I often feel poems have to have some falsity in them, like yeast, or they won’t ‘rise’,’ making precisely the same point as Plath. All such is too intricate a consideration for Hill’s flaring broadsides. That should not really condemn him, since – like all great artists in the process Eliot describes – he is promoting his conception of reality as forcefully as he can. As was Larkin, as was Heaney, and as am I in discussing them, in relation to English poetic tradition, at the expense of various others.

REACTIONARY BEHAVIOUR IS hardly atypical of major English poets ‘policing their patch’ (Hill’s phrase)in the last century. Despite writing so cuttingly of being ‘unready to die / But already at the stage / When one starts to dislike the young,’ Auden nonetheless stands as one of the best examples of the seemingly-predetermined reactionary phase. In quiet contemplation, he had written a poem asking, with some irony, ‘Though I suspect the term is crap, / If there is a Generation Gap, / Who is to blame?’ – and answered himself, ‘Those, old or young, / Who will not learn their Mother-Tongue.’ But pressed more directly on the matter on national TV, ‘What I feel about a lot of the young now,’ he told Michael Parkinson,

is they seem to be bored. Now, when I was young, of course one was often unhappy, but I don’t ever remember, in my life, having been bored … Now there does seem to be, as far as I can see, a boredom. And that upsets me.

The poem, ‘Doggerel by a Senior Citizen’, was written in 1969, and the Parkinson interview given two years later. But beneath Auden, a generation of poets, including Hill, continued to produce verse, some of which is now more widely-appreciated than Auden’s work in that period. A second among them was, of course, Larkin, whose art vitalised being both unhappy and bored: ‘Life is first boredom, then fear’ (‘Dockery and Son’), ‘I, whose childhood | Is a forgotten boredom’ (‘Coming’), and so on. Another – who in many ways was America’s exaggerated equivalent of Larkin – was John Berryman: ‘Life, friends, is boring. We must not say so’ (Dream Songs, 14).

After them comes Seamus Heaney, a man whose influence and taste spread to almost every young poet after 1966, the year of his first collection, Death of a Naturalist. Entering the full pomp of his stardom at the time of his essay ‘Englands of the Mind’, he unifies both Larkin and Hill with Hughes in the context of ‘auditory imagination’, and proceeds to describe a poetry that is really more like his own than theirs:

All of them return to an origin and bring something back, all three live off the hump of the English poetic achievement, all three, here and now, in England, imply a continuity with another England, there and then. All three are hoarders and shorers of what they take to be the real England.

“Reactionary behaviour is hardly atypical of major English poets ‘policing their patch’”

‘England’ and ‘English’ might be interchanged with, or joined by, ‘Ireland’ or ‘Irish’, among other world influences, but the principles outlined here are more akin to the Heaney of North (‘return to an origin and bring something back … imply a continuity with … there and then’) or ‘Postscript’ (‘live off the hump of the [national] poetic achievement,’ instanced by his echoing of Yeats’s ‘The Wild Swans at Coole’) than to any of his chosen three Englishmen. Just as Larkin and Hill seek to define the English line for themselves, so Heaney adapts their styles into his own, making a grounding for his own poetic stance. In short, all these poets create the very tastes by which they aspire to be judged, and try to centre the critical discussion around their own territory, be that stylistic or literal: Larkin has simplicity, Hill has moral ‘metaphysical’ intellectualism, and Heaney has a system of ‘auditory imagination’ drawing on the past and the present in earthy harmony.

All of this, and all of these poets – consciously or otherwise – progress that Eliotic shift, joining and altering the canon that has preceded them, promoting their own values in relation to it. And, lest we think him exempt, that is Eliot’s aim, too – making us think of him internationally, intellectually, near-timelessly – when he asks readers to consider ‘this idea of order, of the form of European, of English literature’ in which

the historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order.

Larkin and Hill nurture their own turns at this, wrestling with the intellectual legacies of Eliot, Thomas, Pound, Yeats and others (not just from the modernists but the whole of poetic history) and coming to mostly different conclusions. Poets constantly assert their presence to that which is around them, simplifying their modus operandi into formulas and statements, often calling upon the shades of the legendary dead to make their opinions and tastes stand up as facts.

In truth, it is near-impossible for factual statements to be made about the tradition and uses of poetry, especially with immediacy, to one’s contemporaries. Whatever Hill and Larkin’s individual claims on him, Edward Thomas remains and will remain exactly as he is: the author of poems written by Edward Thomas. But our perception of those poems – and, for good or ill, of that man – is altered to history by the authority of their prominent advocates. They have each placed themselves in relation to him, if only by way of their evaluations of his qualities.

The same is true of their judgments of their other great predecessor, Eliot, whose principles describe so accurately the process in which they have involved him: the English poetic tradition always finding some way to adapt, incrementally, to what comes next, folding it into, and modifying our perception of, all that has come before.

TOM COOK is currently a postgraduate at the University of Oxford, where he chairs the Twentieth Century Poetry Reading Group; he is also editor of the poetry magazine Ash, co-editor of The Mays 2015, and a staff-member of the English Faculty Library. His writing, mainly poetry, has recently featured in the Spectator, Ambit, the New Statesman and the Times Literary Supplement.

LINDA BESNER talks to NYLA MATUK about her new book